China is a multi-ethnic state. According to the census conducted on 1 November 2000, aside from the Han Chinese, which account for 91।6 percent of the population, there are 55 officially recognized ethnic minorities, or 'national minorities' in Chinese parlance (shaoshu minzu 少数民族), numbering some 106.4 million people all together. These minorities inhabit approximately 60 percent of Chinese territory, often in the strategically more important or sensitive areas along the borders. The largest minorities are the Zhuang (in Guangxi Zhuang Autonomous Region, 15 million); the Manzu, or Manchu (in Northeast China, 9.8 million); Moslems, or Hui (all over China, 8.6 million); Uygur, or Weiwu'er (in Xinjiang Province, 7.2 million); Tujia (Hunan Province, 5.7 million); Mongolians, or Meng (Inner Mongolia, 4.8 million); and Tibetans, or Zang (in Tibet, Qinghai and Sichuan, 4.6 million). The smallest national minorities number only a few thousand members, for example the Gaoshan (Fujian Province) and the Lhoba (Tibet). Many other different ethnic groups (as many as 350) seek official recognition, and at least 15 of them are reported to be officially considered for such recognition.

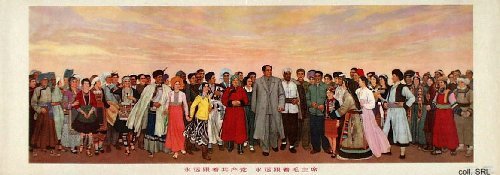

It is a longstanding myth in China that all peoples inhabiting the territory form a homogeneous whole, the Zhonghua minzu 中华民族, or Chinese nationality। This myth is based upon the premise of a shared descent from the mythological Yellow Emperor, the foundation figure of all Chinese who was purportedly born in 2704 BCE. This legend in turn forms the basis for a (racial) nationalism that implies the existence of primal biological and cultural bonds among China’s various ethnic groups. According to scientific research conducted in the early 20th century, the Han nationality was the main branch of all the different population groups in China. This principle forms the basis of China’s minority policy. All minority groups ultimately belong to the same ‘yellow’ race, although they are deemed inferior to it. In other words, the political boundaries of China appeared to be founded on clear biological markers. This line of reasoning has resulted in the official concept that the Chinese people form one big, united family of ethnic groups.

The levels of development of the minorities differ widely, and they are highly heterogeneous both culturally and physically। Some are highly urbanized, while some others practiced slash-and-burn agriculture in the not too distant past. Nonetheless, the Han Chinese always have felt that they are on a civilizing mission and have an obligation to help and defend all those peoples that they consider their inferior, backward (luohou 落后) ‘younger brothers’ (didi 弟弟).

The actual inventory and identification of these minorities only started after the PRC was formally founded। In the Republican period, only five ethnic groups were recognized: Han, Manchu, Mongol, Tibetan and Muslim. In 1950, numerous 'Visit the Nationalities'-teams were sent out to determine what actually constituted minorities, what could be considered as sub-branches of nationalities, or what groups in reality actually belonged to the Han nationality. Initially, the CCP adopted a very broadminded attitude towards the non-Han.

In the early 1930s, viewpoints such as the formation of a federal state granting a high degree of independence to minorities, or even the possibility of secession, were included in the Constitution of the Jiangxi Soviet. In Yan’an, the CCP became aware of the necessity of minority nationality support and appealed to them to support the struggle against Japan. Following Sun Yatsen’s ideas about the minority issue, i.e., that all nationalities in China were equal, had the right to self-determination and would be part of a free and united republic of China, Mao asserted that their spoken and written languages, their manners and customs and their religious beliefs had to be respected.