But no matter how Mao was depicted, he had to be painted hong, guang, liang (红光凉,red, bright, and shining); no grey was allowed for shading, and the use of black was interpreted as an indication that the artist harbored counter-revolutionary intentions. His face was painted usually in reddish and other warm tones, and in such a way that it appeared smooth and seemed to radiate as the primary source of light in a composition. In many instances, Mao's head seemed to be surrounded by a halo which emanated a divine light, illuminating the faces of the people standing in his presence.

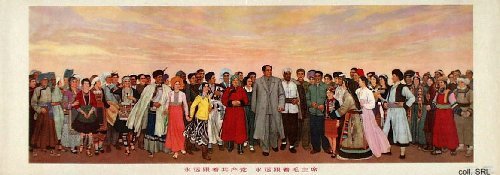

But no matter how Mao was depicted, he had to be painted hong, guang, liang (红光凉,red, bright, and shining); no grey was allowed for shading, and the use of black was interpreted as an indication that the artist harbored counter-revolutionary intentions. His face was painted usually in reddish and other warm tones, and in such a way that it appeared smooth and seemed to radiate as the primary source of light in a composition. In many instances, Mao's head seemed to be surrounded by a halo which emanated a divine light, illuminating the faces of the people standing in his presence. As a super model, every detail of his representations had to be preconceived along ideological lines and invested with symbolic meaning. An extreme example of this is the painting-turned poster Chairman Mao goes to Anyuan. As a consequence of these creative rules governing the depiction of Mao, the more god-like and divorced from the masses he became to be portrayed, often hovering above those masses. And yet, despite this apparent distance, there was something in the Mao images that struck a chord with the people, something recognizable that turned him into an EveryMao. Mao somehow remained united with the people, whether he inspected fields, shook hands with the peasants, sat down with them, and shared a cigarette with them; whether he inspected factories or infra-structural works, joked with the workers, and possibly shared a cigarette with them; whether he was dressed in military uniform, discussing strategy with military leaders, inspected the rank-and-file, or mingled with contingents of Red Guards; whether he stood on the bow of a ship, dressed in a terry cloth bathrobe after an invigorating swim in the Yangzi River; whether he headed a column of representatives of the national minorities; or received a delegation of foreign visitors.

As a super model, every detail of his representations had to be preconceived along ideological lines and invested with symbolic meaning. An extreme example of this is the painting-turned poster Chairman Mao goes to Anyuan. As a consequence of these creative rules governing the depiction of Mao, the more god-like and divorced from the masses he became to be portrayed, often hovering above those masses. And yet, despite this apparent distance, there was something in the Mao images that struck a chord with the people, something recognizable that turned him into an EveryMao. Mao somehow remained united with the people, whether he inspected fields, shook hands with the peasants, sat down with them, and shared a cigarette with them; whether he inspected factories or infra-structural works, joked with the workers, and possibly shared a cigarette with them; whether he was dressed in military uniform, discussing strategy with military leaders, inspected the rank-and-file, or mingled with contingents of Red Guards; whether he stood on the bow of a ship, dressed in a terry cloth bathrobe after an invigorating swim in the Yangzi River; whether he headed a column of representatives of the national minorities; or received a delegation of foreign visitors. As the Cultural Revolution unfolded, Mao became a regular presence in every home, either in the form of his official portrait, or as a bust or other type of statue. Not having the Mao portrait on display indicated an apparent unwillingness to go with the revolutionary flow of the moment, or even a counter-revolutionary outlook, and refuted the central role Mao played not only in politics, but in the day-to-day affairs of the people as well. The formal portrait often occupied the central place on the family altar, or at least the spot where that altar had been located before it had been demolished by Red Guards in the early days of the Cultural Revolution. This added to the already god-like stature of Mao as it was created in propaganda posters.

As the Cultural Revolution unfolded, Mao became a regular presence in every home, either in the form of his official portrait, or as a bust or other type of statue. Not having the Mao portrait on display indicated an apparent unwillingness to go with the revolutionary flow of the moment, or even a counter-revolutionary outlook, and refuted the central role Mao played not only in politics, but in the day-to-day affairs of the people as well. The formal portrait often occupied the central place on the family altar, or at least the spot where that altar had been located before it had been demolished by Red Guards in the early days of the Cultural Revolution. This added to the already god-like stature of Mao as it was created in propaganda posters.  The days were structured around the ritual of "asking for instructions in the morning, thanking Mao for his kindness at noon, and reporting back at night". This involved bowing three times, the singing of the national anthem, reading passages from the Little Red Book in front of Mao's picture or bust, and would end with wishing him 'Ten thousand years'. In the mornings, everybody would announce what efforts they would make that day for the revolution. In the evenings, people would report on their accomplishments or failures and announce their resolutions for the next day. The rituals were often accompanied by dancing the 'loyalty dance' (zhongzi wu 忠字舞), which did not involve much more than stretching one's arms from the heart to Mao's portrait. The movements, originating from a folk dance popular in Xinjiang, was accompanied by the song "Beloved Chairman Mao".

The days were structured around the ritual of "asking for instructions in the morning, thanking Mao for his kindness at noon, and reporting back at night". This involved bowing three times, the singing of the national anthem, reading passages from the Little Red Book in front of Mao's picture or bust, and would end with wishing him 'Ten thousand years'. In the mornings, everybody would announce what efforts they would make that day for the revolution. In the evenings, people would report on their accomplishments or failures and announce their resolutions for the next day. The rituals were often accompanied by dancing the 'loyalty dance' (zhongzi wu 忠字舞), which did not involve much more than stretching one's arms from the heart to Mao's portrait. The movements, originating from a folk dance popular in Xinjiang, was accompanied by the song "Beloved Chairman Mao". In the early 1970s, the extreme and more religious aspects of Mao's personality cult were being dismantled. In propaganda posters, proxies such as Lei Feng—or one of his reincarnations—and Chen Yonggui (the model Party secretary of Dazhai Commune) often replaced Mao himself. This did not diminish the adulation of Mao, who continued to lead the CCP as it was being rebuilt. The excesses committed by the people during the heyday of the Cultural Revolution in the late 1960s, including the embarrassing habit of "3,000 years of emperor-worshipping tradition" which Mao himself had consciously promoted and in which he himself had basked, were attributed to Lin Biao, who had—quite literally—fallen from grace in 1971. Similarly, the Army, the former "great school of Mao Zedong Thought", no longer functioned as a model for the people. Instead, the "fine work style" of the CCP and the masses were what the army needed to learn from.

In the early 1970s, the extreme and more religious aspects of Mao's personality cult were being dismantled. In propaganda posters, proxies such as Lei Feng—or one of his reincarnations—and Chen Yonggui (the model Party secretary of Dazhai Commune) often replaced Mao himself. This did not diminish the adulation of Mao, who continued to lead the CCP as it was being rebuilt. The excesses committed by the people during the heyday of the Cultural Revolution in the late 1960s, including the embarrassing habit of "3,000 years of emperor-worshipping tradition" which Mao himself had consciously promoted and in which he himself had basked, were attributed to Lin Biao, who had—quite literally—fallen from grace in 1971. Similarly, the Army, the former "great school of Mao Zedong Thought", no longer functioned as a model for the people. Instead, the "fine work style" of the CCP and the masses were what the army needed to learn from.

After the Cultural Revolution, the propagation of the divine presence and the accomplishments of the supreme leader would never again be repeated in the same intensity, sophistication, and mind-numbing density. In the China of economic reforms and Open Door policy, the production of posters containing ideological exhortations was replaced more and more in the 1980s by those stressing economic construction, or even ordinary commercial advertisements. In the early 1990s, a resurgence of the popular belief in the protective qualities of a truly god-like Mao did take place. This MaoFever coincided with the marking of the centenary of his birth. The continued importance of Mao as a political symbol is attested to by the issuance of a new 100-yuan bank note in 1999 to commemorate the 50th anniversary of the PRC: the image of a youngish Mao graces the bill. He moreover appeared in a special series of posters, also showing Deng Xiaoping and Jiang Zemin (the so-called "three generations of leaders"), to mark the occassion.

After the Cultural Revolution, the propagation of the divine presence and the accomplishments of the supreme leader would never again be repeated in the same intensity, sophistication, and mind-numbing density. In the China of economic reforms and Open Door policy, the production of posters containing ideological exhortations was replaced more and more in the 1980s by those stressing economic construction, or even ordinary commercial advertisements. In the early 1990s, a resurgence of the popular belief in the protective qualities of a truly god-like Mao did take place. This MaoFever coincided with the marking of the centenary of his birth. The continued importance of Mao as a political symbol is attested to by the issuance of a new 100-yuan bank note in 1999 to commemorate the 50th anniversary of the PRC: the image of a youngish Mao graces the bill. He moreover appeared in a special series of posters, also showing Deng Xiaoping and Jiang Zemin (the so-called "three generations of leaders"), to mark the occassion.

No comments:

Post a Comment