In 1962, Mao advocated the Socialist Education Movement (SEM), in an attempt to 'inoculate' the peasantry against the temptations of feudalism and the sprouts of capitalism that he saw re-emerging in the countryside. Large doses of didactic politicized art, whether figurative or literary, were produced as serum for this inoculation process. The Party organization saw the initiatives proposed by Mao and his even more radical followers as interfering with its successful program of economic rehabilitation that had started after the Great Leap Forward. Given the scope of the problems, the Party preferred more technocratic solutions and was averse to Mao's millennial visions. There are no indications that open opposition to Mao actually existed, although the Chairman believed there was. He was truly convinced that the more moderate leaders were trying to steal his place in history by subverting the nature of the revolution he had fought for. In order to reclaim his rightful place at the apex of power and to oust those he perceived as revisionists, Mao turned towards the People's Liberation Army, the only organization he still deemed ideologically correct.

In 1962, Mao advocated the Socialist Education Movement (SEM), in an attempt to 'inoculate' the peasantry against the temptations of feudalism and the sprouts of capitalism that he saw re-emerging in the countryside. Large doses of didactic politicized art, whether figurative or literary, were produced as serum for this inoculation process. The Party organization saw the initiatives proposed by Mao and his even more radical followers as interfering with its successful program of economic rehabilitation that had started after the Great Leap Forward. Given the scope of the problems, the Party preferred more technocratic solutions and was averse to Mao's millennial visions. There are no indications that open opposition to Mao actually existed, although the Chairman believed there was. He was truly convinced that the more moderate leaders were trying to steal his place in history by subverting the nature of the revolution he had fought for. In order to reclaim his rightful place at the apex of power and to oust those he perceived as revisionists, Mao turned towards the People's Liberation Army, the only organization he still deemed ideologically correct.

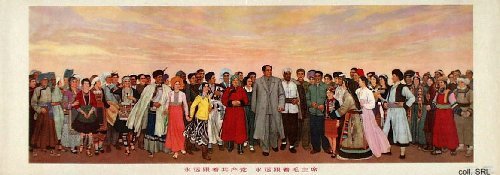

Mao already had appeared prominently on propaganda posters as far back as the 1940s, despite his ambiguous warnings against a personality cult. The intensity of his portrayal in the second half of the 1960s, however, was unparalleled. Under Lin Biao, the PLA increasingly was employed to bolster the personality cult around Mao, and thus to produce art that would contribute to the construction of Mao's god-like image. All this took place with Mao's consent. Already before the compilation of the Quotations from Chairman Mao (Mao zhuxi yulu 毛主席语录, the 'Little Red Book', published in May 1964) for use by the armed forces, the PLA had been turned into "a great school of Mao Zedong Thought". The army became the driving force behind the campaign to study Mao's Quotations.

Mao already had appeared prominently on propaganda posters as far back as the 1940s, despite his ambiguous warnings against a personality cult. The intensity of his portrayal in the second half of the 1960s, however, was unparalleled. Under Lin Biao, the PLA increasingly was employed to bolster the personality cult around Mao, and thus to produce art that would contribute to the construction of Mao's god-like image. All this took place with Mao's consent. Already before the compilation of the Quotations from Chairman Mao (Mao zhuxi yulu 毛主席语录, the 'Little Red Book', published in May 1964) for use by the armed forces, the PLA had been turned into "a great school of Mao Zedong Thought". The army became the driving force behind the campaign to study Mao's Quotations. A study session with the Quotations "... supplied the breath of life to soldiers gasping in the thin air of the Tibetan plateau; enabled workers to raise the sinking city of Shanghai three-quarters of an inch; inspired a million people to subdue a tidal wave in 1969, inaccurate meteorologists to forecast weather correctly, a group of housewives to re-invent shoe polish, surgeons to sew back severed fingers and remove a ninety-nine pound tumor as big as a football."

A study session with the Quotations "... supplied the breath of life to soldiers gasping in the thin air of the Tibetan plateau; enabled workers to raise the sinking city of Shanghai three-quarters of an inch; inspired a million people to subdue a tidal wave in 1969, inaccurate meteorologists to forecast weather correctly, a group of housewives to re-invent shoe polish, surgeons to sew back severed fingers and remove a ninety-nine pound tumor as big as a football." The PLA also supplied most of the behavioural models that embodied the "spirit of a screw" (luosiding jingshen 螺丝钉精神) by blindly following the instructions from the Party and/or superiors and attachment to the larger group. The best known of these were model soldiers as Lei Feng, Wang Jie, Dong Cunrui, and Ouyang Hai.

The PLA also supplied most of the behavioural models that embodied the "spirit of a screw" (luosiding jingshen 螺丝钉精神) by blindly following the instructions from the Party and/or superiors and attachment to the larger group. The best known of these were model soldiers as Lei Feng, Wang Jie, Dong Cunrui, and Ouyang Hai.

Logically, the Army became responsible for art. This art should unite and educate the people, inspire the struggle of revolutionary people and eliminate the bourgeoisie. Art had to be guided by Mao Zedong Thought, its contents had to be militant and to reflect real life. Proletarian ideology, communist morale and spirit, revolutionary heroism were the messages of a new type of hyper-realism that took precedence over style and technique and that differed in all aspects from art creation until then. In the PLA paintings of the time, the color red featured heavily; it symbolized everything revolutionary, everything good and moral; the color black, on the other hand, signified precisely the opposite. Color symbolism continued to be important in the following years, not only in visual propaganda, but in printed propaganda as well.

Logically, the Army became responsible for art. This art should unite and educate the people, inspire the struggle of revolutionary people and eliminate the bourgeoisie. Art had to be guided by Mao Zedong Thought, its contents had to be militant and to reflect real life. Proletarian ideology, communist morale and spirit, revolutionary heroism were the messages of a new type of hyper-realism that took precedence over style and technique and that differed in all aspects from art creation until then. In the PLA paintings of the time, the color red featured heavily; it symbolized everything revolutionary, everything good and moral; the color black, on the other hand, signified precisely the opposite. Color symbolism continued to be important in the following years, not only in visual propaganda, but in printed propaganda as well.  Mao's wife Jiang Qing supported the artistic direction set by the PLA. The conceptual dogmas and theatrical conventions provided by the model operas (yangbanxi 样板戏) that she supported also became the standard in the visual arts. For the stage, she formulated the 'three prominences' (三突出,stress positive characters; stress the heroic in them; stress the central character of the main characters). In the arts, this was translated as: the subjects were to be portrayed realistically, and they were always to be in the centre of the action, flooded with light from the sun or from hidden sources. Moreover, when we look at the propaganda posters of these years, it always seems as if we, the spectators, are looking upward, as if the action is indeed taking place upon a stage.

Mao's wife Jiang Qing supported the artistic direction set by the PLA. The conceptual dogmas and theatrical conventions provided by the model operas (yangbanxi 样板戏) that she supported also became the standard in the visual arts. For the stage, she formulated the 'three prominences' (三突出,stress positive characters; stress the heroic in them; stress the central character of the main characters). In the arts, this was translated as: the subjects were to be portrayed realistically, and they were always to be in the centre of the action, flooded with light from the sun or from hidden sources. Moreover, when we look at the propaganda posters of these years, it always seems as if we, the spectators, are looking upward, as if the action is indeed taking place upon a stage. The subjects were represented hyper-realistically, as ageless, larger-than-life peasants, soldiers, workers and educated youth in dynamic poses. Their strong and healthy bodies functioned as metaphors for the strong and healthy productive classes the State wanted to propagate. In line with the egalitarian character of the Maoist culture of the body, the gender distinctions of the subjects were by and large erased—something that was also attempted in real life. Men and women alike had stereotypical, "masculinized" bodies; they were dressed in cadre grey, army green or worker/peasant blue; their hands and feet often were absurdly big in relation to the rest of their bodies; and their faces, including short-cropped hairdos and chopped-off pigtails, were done according to a limited standard repertoire of acceptable examples. Even in the many propaganda posters that featured Mao, the Chairman was subjected to these stylistic dictates. As a result, he appeared as a muscular super-person.

The subjects were represented hyper-realistically, as ageless, larger-than-life peasants, soldiers, workers and educated youth in dynamic poses. Their strong and healthy bodies functioned as metaphors for the strong and healthy productive classes the State wanted to propagate. In line with the egalitarian character of the Maoist culture of the body, the gender distinctions of the subjects were by and large erased—something that was also attempted in real life. Men and women alike had stereotypical, "masculinized" bodies; they were dressed in cadre grey, army green or worker/peasant blue; their hands and feet often were absurdly big in relation to the rest of their bodies; and their faces, including short-cropped hairdos and chopped-off pigtails, were done according to a limited standard repertoire of acceptable examples. Even in the many propaganda posters that featured Mao, the Chairman was subjected to these stylistic dictates. As a result, he appeared as a muscular super-person.

As the Great Teacher, the Great Leader, the Great Helmsman, the Supreme Commander, Mao came to dominate the propaganda art of the first half of the Cultural Revolution. His image was considered more important than the occasion for which a particular work of propaganda art was designed: in a number of cases, identical posters dedicated to Mao were published in different years bearing different slogans, i.e., serving different propaganda causes.

Mao could be depicted as a benevolent father, bringing the Confucian mechanisms of popular obedience into play. Or he was portrayed as a wise statesman, an astute military leader or a great teacher; to this end, artists represented him in the vein of the statues of Lenin, which had started to appear in the early 1920s in the Soviet Union. Another group of posters visually recounted the more illustrious of his historical deeds.

No comments:

Post a Comment